In previous posts, our team has discussed the importance of designing courses with the students in mind. However, instructional designers should also consider the needs of the faculty while designing courses, especially their cognitive load. Developed by John Sweller in 1988, cognitive load theory notes that each of us has a mental schema (i.e., knowledge base) developed from “a series of structures that enable us to solve problems and think. It also allows us to look at several different elements within a lesson or experience and treat those elements as just one whole element” (Pappas, 2024). However, our minds can only retain so much information. When our mental schemas become overwhelmed with too much information, we experience cognitive overload.

Hartman (2023) asserts we need to ease faculty’s cognitive load rather than simply removing tasks and responsibilities from them. Those who work in instructional design and eLearning can improve the teaching experience by designing courses that remove potentials for cognitive overload. In this post, we’ll explore how being cognizant of faculty’s cognitive load can reduce burnout and turnover. Designing courses in this manner includes identifying specific and attainable weekly learning objectives, creating and curating relevant content, and being selective about platforms and tools.

Weekly learning objectives: Building the foundation

Weekly learning objectives set the foundation for a course’s design and curriculum by providing signposts of what the students will learn. These signposts, in turn, create a map that reveals how the students will arrive at the overall course learning outcomes, the final destination at the end of a course.

Weekly learning objectives describe what the students will be able to achieve after engaging in a week’s assignments and activities. Assignments and activities can become redundant when multiple assignments are created to meet each individual weekly learning objective. This creates an overwhelming workload for both faculty and students. Pappas (2024) concurs, asserting that limiting redundancy in online courses “reduces the amount of unnecessary repetition-induced load that is put upon the working memory.”

As you create your weekly learning objectives:

- Keep your audience in mind.

- Begin with a brief description of the context in which the learning objective is relevant.

- Include active verb describing what a learner will know, be able to do, or value.

- Conclude with a brief description of the content, skill or value connected to the objective. (Mager, 1984; Straub, 2024)

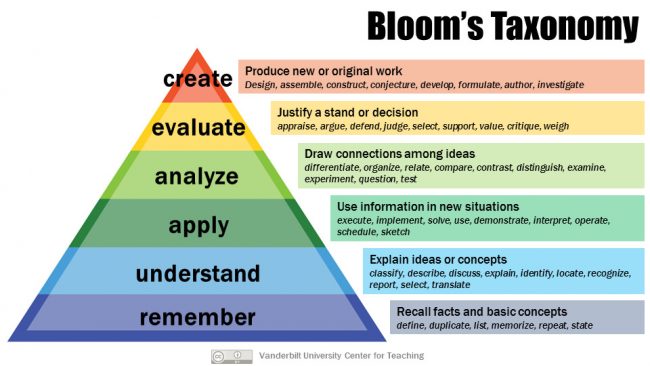

In Bloom’s Taxonomy, an active verb is the crux of any weekly learning objective. Developed in 1956 by Benjamin Bloom and his colleagues and revised in 2001 by a group of psychologists, curriculum theorists, and instructional researchers, Bloom’s Taxonomy is a pedagogical pyramid that describes the cognitive processes students engage with to attain knowledge (Armstrong, 2010; Empire State University, n.d.; Straub, 2024). For example, drill and practice quizzes can align with lower levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy while reducing the need for faculty grading, especially when they’re created in a learning management system (LMS).

Empire State University (n.d.) cleverly illustrates overall course learning outcomes and weekly learning objectives in terms of baking a cake:

Course Learning Outcome:

- Bake a cake

Weekly Learning Objectives:

- Measure ingredients

- Mix ingredients

- Set oven temperature

- Identify the point of doneness of a cake

- Etc.

Curriculum can be designed in different ways based on the length and pace of the course. For example, assignments might cover one or several learning objectives addressed in a week (Empire State University, n.d.). So, a weekly learning objective in this scenario could look like this:

By the end of this week the student will be able to understand how to measure and mix ingredients when baking a cake.

Once you’ve determined your weekly learning objectives and how they will help the students achieve the overall course learning outcomes, you can begin to design the curriculum for your course, which comes down to relevant content creation and curation.

Content creation vs. content curation

Designing courses not only involves understanding how and what to teach, but also relevant content creation and curation. Considering faculty and student needs allows us to curate relevant content—which helps faculty determine how and what to teach. In my series on Keller’s ARCS Model for Motivation, I discuss the importance of relevance in designing and teaching courses. Strategies used to enhance relevance include: value, experience, present worth, future usefulness, need matching, modeling, choice, and engagement.

A content creator is the equivalent of being an author, since the content is created from scratch. In contrast, a content curator is the equivalent of being a librarian, since the content is chosen from other sources such as videos, journal articles, podcasts, etc. to supplement the course (Virtual College, 2018). In both cases, the content “needs to be filtered so only the relevant information is left” (Virtual College, 2018). In addition, curated content “should only be used as part of a well-rounded approach,” meaning a course should not be bogged down with more content and assignments than faculty and students can handle in a given week (Virtual College, 2018).

Just enough technology

In the process of content creation and curation, instructional designers should consider how the technology delivering the content fits into the design of a course. Hartman (2023) discourages instructional designers from being, platform [and I would add tool] happy. Each platform requires different skills, instructions, etc. in addition to the information the faculty are already trying to retain from navigating and using the LMS, so requiring faculty to grade assignments in multiple platforms and tools can be taxing on their cognitive load. Our university transitioned to a new LMS last summer. In addition to mastering the new LMS, our programs sometimes use additional platforms and/or tools for students’ assignments that are outside of the LMS. We’re working to reduce additional workload by recommending tools within the LMS.

Conclusion

As instructional designers, we need to collaborate with subject matter experts to design courses with the faculty’s cognitive load in mind. Designing courses that are not redundant or overcrowded with content, not only “ensures that all students have optimal conditions in which to demonstrate their learning” but also enables faculty to “evaluate students’ knowledge and skills fairly and accurately” without being overwhelmed or burned out (Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning, n.d.). The more you can make a course’s weekly learning objectives, content, and technology relevant, the less overwhelming your course will be—which faculty and students will thank you for.

References

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved January 23, 2025.

Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Equitable assignment design. Indiana University Bloomington.

Empire State University. (n.d.). Getting started with design. Digital Learning – SUNY Empire State University.

Hartman, E. (2023, February 15). 6 things you can do to ease educator cognitive load. GoGuardian.

Mager, R. F. (1984). Preparing instructional objectives. Fearon Publishers.

Pappas, C. (2024, May 16). Cognitive load theory and instructional design. eLearningIndustry.

Straub, E. O. (2024, January 15). Learning objectives and outcomes. Online Teaching – University of Michigan.

Virtual College. (2018, October 21). Content creation vs content curation in e-learning. Netex learning.

One thought on “Designing Courses with Faculty Cognitive Loads in Mind”